The muffled echo of a closed-door session, held within a republican institution whose brilliance was once the beacon of French thought, resonates today as a dissonant premonition in the vast amphitheater of liberal democracy.

The invitation of Peter Thiel, emblematic figure of a techno-oligarchy with transcendent ambitions, to the Academy of Moral and Political Sciences, beyond mere worldly anecdote or simple intellectual curiosity, can only be analyzed as the manifest symptom of a profound drift, even an insidious perversion, of the moral and intellectual compass of our societies.

The question is no longer whether we should listen to all voices, including the most radical ones, in a Socratic approach of confronting ideas (a noble but dangerously naive ideal in the face of cultural conquest strategies) but rather to denounce the disastrous intellectual orientation that would make the "powerful" holders of technological means potential guides to enlighten us about the nature and future of democracy.

This premise is not only fallacious but also profoundly deleterious, threatening to redefine the very foundations of our social pact around principles that are intrinsically hostile to it.

The opacity that surrounded this meeting, this deliberately orchestrated closed session, is not a minor detail; it constitutes the first sign of a profound malaise, an attempt to remove from public view an ideological confrontation whose stakes far exceed academic circles.

Why, indeed, such secrecy? The argument, often advanced, of a need to create a laboratory of ideas where the most iconoclastic theses can be analyzed without the thunderbolts of public opinion, reveals itself, upon closer examination, to be a superficial, even cynical justification. Such an argument assumes that Thiel's discourse would be so fragile that it could not withstand the light of day, or, conversely, that it would contain such subversive power that it should be contained within the protective limits of the Academy to avoid any premature contamination of the social body. Neither of these interpretations is reassuring.

Democracy, by essence, feeds on light, transparency and public debate. It is the place where ideas, even the most disturbing ones, are subjected to collective criticism, shared rationality and citizen examination. Confining the discussion of a "radically critical" thought of democracy within a restricted elite, however erudite it may be, amounts to granting this thought legitimacy by exception, a sort of derogation from the democratic principle of open debate. It is to isolate it to better domesticate it, or worse, to inoculate it gently into spheres of influence without the filter of popular contradiction. Secrecy, in this context, is not a protective shield of thought, but a cloak concealing the true motivations, hesitations or complacencies that could be revealed if the exchange took place under the implacable gaze of the public square. It suggests embarrassment, an implicit awareness of the problematic nature of the exercise, or a deliberate will to control the narrative and impact of these ideas, even if it means giving them institutional respectability without fully assuming the consequences before the community. This closed session is less a guarantee of intellectual serenity than a back door opened to the elite's inner circle, conducive to ideological slippages that popular vigilance could have, and should have, countered.

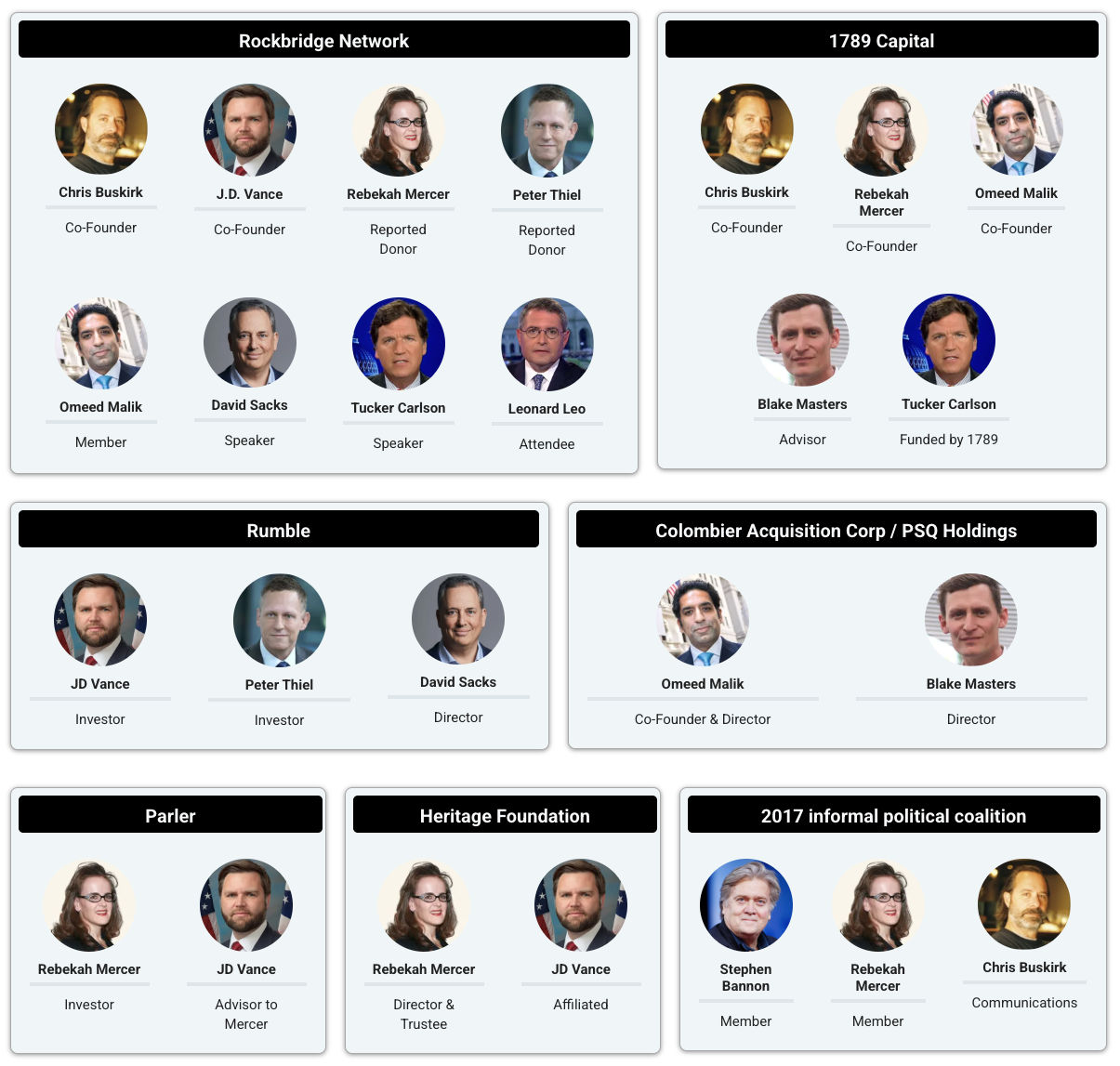

The real questions and motivations of this "working group" on "the future of democracy" deserve analysis with redoubled perspicacity, because stated intentions often hide more complex agendas, even deep flaws in understanding contemporary challenges. The proclaimed idea of hearing "dissonant voices" or "adversaries of democracy" to better analyze and refute them is, in principle, laudable. The problem arises when this confrontation transforms, objectively, into a symbolic platform that confers prestige and legitimacy to ideas of anti-democratic nature. The Peter Thiel case is not a simple neutral "object of study," an intellectual specimen to observe in a laboratory. He is a powerful actor, an ideologist endowed with considerable financial means, whose theses (whether his skepticism toward representative democracy, his hostility to multiculturalism, his fantasy of ruling elites, or his political theology of the Antichrist and the katechon) are not simple academic speculations. They are justifications for a politics of power, of exception, and a rollback of social protections, already at work in certain political and technocratic circles.

The real motivations could therefore go beyond simple critical analysis. They could reside in a guilty fascination, a latent temptation within certain conservative elites –and even beyond– for authoritarian solutions, for order in the face of the perceived chaos of a democracy deemed inefficient or excessively egalitarian. Hervé Gaymard, coordinator of the group, with his sensitivity to institutional crises and political theology, perhaps embodies this intellectual fringe. His quest for an "understanding" of these radical currents can easily slip toward a form of complacency, where one exposes oneself to a thought without fully measuring its corrosive potential, under the pretext of sophisticated intellectual curiosity. The danger lies precisely in this posture: opening up to anti-democratic discourses, far from neutralizing them, trivializes them, normalizes them, and insidiously shifts the boundaries of the speakable and thinkable. The real issue is not understanding "what Thiel thinks," but understanding why republican institutions feel the need, or the right, to confer on such thoughts a platform of this magnitude, risking implicitly validating the idea that democratic principles are so weakened that they must be "reformed" by such dark visions.

This working group, under the cover of healthy introspection, could well be, knowingly or not, an experimental ground for a dangerous ideological restructuring.

This invitation, the closed session that draped it, and the ambiguous motivations that underpinned it, are all warning signs of a disturbing intellectual and political mutation. Are we not, indeed, in the process of assimilating "dark enlightenment" as foundational to a new state of world order? The charged expression evokes a form of counter-Enlightenment, a return to pre-democratic doctrines, where reason would no longer be the guide of collective emancipation, but the instrument of technocratic and elitist domination, often tinged with eschatology or historical fatalism. Thiel, by combining intransigent Catholicism with an exaltation of the victorious entrepreneur and a rollback of social protections, proposes an ideology that transcends traditional divisions, merging radical conservatism with a futuristic vision of technology. This synthesis is reminiscent of reactionary and anti-Enlightenment thinkers (Joseph de Maistre, Louis-Gabriel-Ambroise de Bonald, Jean-Jacques Rousseau to name just a few) who, in the past, sought to deconstruct the foundations of freedom and equality under various pretexts.

Today, the technological argument offers new attire to these old temptations. The "dark enlightenment" manifests through this belief that the complexity of the modern world, accelerated by technology, would render obsolete the slowness and compromises of representative democracy. It advocates the efficiency of governance by experts, "providential men," or algorithms, to the detriment of popular sovereignty.

This assimilation operates on several fronts. First, through symbolic legitimation. When an Academy of the Republic welcomes such figures, it offers them an intellectual carte blanche, a quasi-state respectability that makes their theses less marginal and more "audible" in the spheres of power. The risk is not that Thiel "converts" the Academy, but that the Academy, by welcoming him, participates despite itself in normalizing these discourses in the eyes of elites. Then, through the growing porosity between the technological world and spheres of political decision. The "powerful" of tech, far from being mere inventors, have become major geopolitical actors, whose influence exceeds that of many states. Their worldviews, their ideologies, their "philosophies" (however rudimentary or fanciful they may sometimes be) do not remain confined to laboratories or boardrooms. They are injected into public debate, often via think tanks, influenced media or, as here, academic institutions. The fantasy of a "world government" fought by Thiel, ironically, finds a perverse echo in the reality of globalized technological power that answers to very few democratic accounts. This slide toward a new world order is not a manifest coup de force, but a progressive erosion of democratic foundations, under the seductive charm of innovation and efficiency. The "dark enlightenment" does not frontally oppose reason, but perverts it by putting it at the service of anti-democratic ends, reducing it to instrumental rationality, detached from any ethical or egalitarian political consideration. It promises a "better" or "more stable" world in exchange for freedom and collective autonomy.

The vision of a world where tech billionaires, crowned with their entrepreneurial success and their alleged ability to "disrupt" the old world, pose as oracles of democracy, is a dangerous chimera. Their legitimacy rests on accumulated wealth and mastery of technological tools, not on a popular mandate or proven political wisdom. They are builders of economic empires, not architects of the common good. Their "vision" of democracy is inevitably filtered through their economic interests, their ideological prejudices and their disdain for the control and balance mechanisms that democracy has patiently constructed. They embody a technocratic elite that aspires to lead the world not through consensus, but through the force of innovation and the alleged inevitability of technical progress. In doing so, they propose a form of government that tends to empty democracy of its substance, reducing it to an empty shell where essential decisions are made by unelected actors, in the name of technical expertise or self-proclaimed prophetic vision.

The critical debate that followed this invitation, although sometimes marginalized, is a necessary counterweight, a glimmer of hope in this dark picture. It reveals that, despite attempts at normalization, part of the intellectual and citizen community clearly perceives the risk and strives to name it.

The APPEP, university tribunes, in-depth analyses, are all intellectual shields raised against the rising tide of "dark enlightenment." However, this resistance is fragile. It must face powerful forces, endowed with colossal means and unprecedented capacity for influence. The deepest danger perhaps lies in progressive indifference, in the social body's habituation to these discourses that, just yesterday, would have been judged extravagant or alarming. When institutions supposed to be the guardians of the Republic and its values lend themselves to such exercises, they contribute, through their aura and historical legitimacy, to lowering vigilance thresholds, to shifting the "window of the speakable" toward authoritarian horizons.

In final analysis, the Peter Thiel at the Academy episode is much more than a simple controversy. It is a powerful metaphor of our era, a mirror held up to liberal democracy that reveals its intrinsic fragilities in the face of the sirens of technocracy and neo-authoritarianism. The "dark enlightenment" is not a distant abstraction; it is an active force, manifesting in elite complacency, attraction to order in the face of disorder, and the temptation to entrust our collective destiny to "powerful" figures who promise quick and efficient solutions, at the price of our most fundamental freedoms. Refusing these self-proclaimed guides means reaffirming the primacy of popular sovereignty, the inalienable value of equality and the imperative necessity of transparent and inclusive public debate. It means choosing the democracy of light against technocratic obscurantism that seeks to impose itself as the new world order. The price of vigilance is eternal, and never has this maxim been more relevant than at a time when the boundaries of democratic thought are insidiously undermined from within, under the sometimes consenting gaze of those who should be its most ardent defenders.

It is time to unmask these "dark enlightenment" forces and to reaffirm, with strength and conviction, that technological power confers no legitimacy to dictate the terms of democratic coexistence.